As Fadil Sulejmani greeted students and faculty of the new State University of Tetova, he uttered words likely never spoken before – or since – to mark the inauguration of a school.

As Fadil Sulejmani greeted students and faculty of the new State University of Tetova, he uttered words likely never spoken before – or since – to mark the inauguration of a school.

“We want pens and notebooks,” Sulejmani told the crowd, “not violence.”

Despite his pleas and his hopes, terrible unrest awaited the trailblazers of ethnic Albanian higher education in Macedonia, even on that day in February 1995.

Local police decked out in riot gear tried to force their way into the classrooms. They did not succeed. Members of the local community courageously turned out en masse to form a human blockade.

Yet the government would continue to harass and intimidate Tetova for several years.

Sulejmani himself, a professor of Albanian at the University of Prishtina for 23 years before he helped to found Tetova with other Albanian intellectuals, eventually was arrested and sentenced to 30 months in prison, although he was released after one year.

His only crime? Daring to provide higher education to ethnic Albanians.

To Patrick Roberts, associate professor in the Department of Leadership, Educational Psychology and Foundations, the story of Tetova is too compelling – and too important – to ignore.

“Ethnic Albanians are a minority, more or less marginalized with limited access to higher education,” says Roberts, who also serves as faculty director of the College of Education’s Blackwell History of Education Museum. “Their story is a very powerful lesson of how higher education should never be taken for granted.”

Fortunately, cameras caught it all.

Nearly 70 reproductions of photographs that depict the university’s tumultuous existence are coming to the Blackwell for a five-month exhibition.

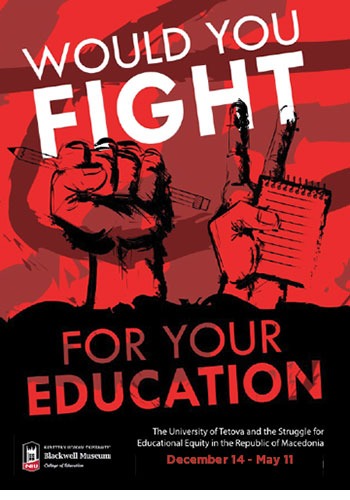

Called “The University of Tetova and the Struggle for Educational Equity in the Republic of Macedonia,” the exhibition features nearly70 reproduced photographs.

Museum visitors also can read first-person narratives written by four people who were involved in the founding or the early years of Tetova.

Roberts began thinking last December about bringing the images to DeKalb, as he and others from NIU visited Tetova for an international conference at the Center for Peace and Transcultural Communication, a joint venture between the two universities.

“The NIU folks who were there were taken to the University of Tetova’s museum, in the small building where the first classes were held,” he says. “In this small museum were many, many photographs taken over the years that told the story of the university’s founding and its status, in many respects, as an illegal university. It was not recognized by the government.”

Steve Builta, director of Technology Innovation and Learning Services for the College of Education, quickly bought into Roberts’ vision. Builta compares Tetova’s battle for educational rights to the U.S. struggles to desegregate its K-12 schools decades ago.

“It’s very compelling. It’s a fantastic story to tell about a place in the world that not many of our students know much about, and people will be fascinated,” Builta says. “It will be interesting for people to think about the fact that we don’t have to fight for our university education in the way they did.”

Rachelle Wilson-Loring, graduate assistant for the Blackwell, the Department of Anthropology and the Pick Museum of Anthropology, has helped to curate and install the Tetova exhibition.

Before beginning the curation process, she knew nothing about the University of Tetova and only a little about Macedonia.

“I remember the war and the refugees, but I was too young to understand the nuances,” Wilson-Loring says. “This exhibition has really made me examine what was going on, and it’s a familiar story: the fight for education. I believe that education is a human right, and being able to tell this story for them – and to show their fight – is really empowering to me.”

An “anthropologist by nature,” she hopes that visitors to the exhibition adopt an international view of education, considering that what happens globally impacts the United States, and then question themselves and others about finding the best paths to progress.

“Education shouldn’t be a stagnant thing, and we have been keeping it that way for too long,” she says. “I hope people understand why the ethnic Albanians were fighting for this – a university, teaching in the Albanian language, teaching Albanian history – and fighting for the survival of their culture.”

Students should take personal inspiration from the photographs, Roberts adds.

“This is a really relatable story, with lessons of how a group of committed students, with the help of their community and their professors, can really fight for this right to a quality life and education,” Roberts says.

“We hope to energize our own students to think of themselves as activists,” he adds, “and the roles they can play to be advocates or leaders in any social movement they feel impassioned about.”

Guided tours for faculty and students are planned for the spring semester, Wilson-Loring says. The exhibition closes Friday, May 11.

The Blackwell is located in the Learning Center on the lower level of Gabel Hall. For more information, call 815-753-1236 or email blackwell@niu.edu.