The NIU Art Museum will sponsor a screening and discussion of Japanese cinematographer Akira Kurosawa’s 1957 classic “Throne of Blood” at 7 p.m. Thursday, April 30.

The NIU Art Museum will sponsor a screening and discussion of Japanese cinematographer Akira Kurosawa’s 1957 classic “Throne of Blood” at 7 p.m. Thursday, April 30.

NIU history and language professors E. Taylor Atkins and John R. Bentley will moderate this re-interpretation of Macbeth at the Egyptian Theatre, 135 N. Second St. Doors open at 6:30 p.m. Admission is $7 for adults and $5 for students, seniors and NIU Art Museum members.

Stuart Henn, coordinator of marketing and education at the NIU Art Museum, took a moment to talk about the film with the moderators of the discussion and screening.

Henn: What first drew you to this particular film by Kurosawa for the screening?

Atkins: I first saw this film when I was an exchange student in Japan in the fall of 1988. One of the faculty at our school, Kansai Gaidai, would show classic Japanese films on Friday afternoons. I think I attended every one. “Throne of Blood” was one of the most memorable and mesmerizing. When Museum Director Jo Burke asked if I knew a movie that “blended East and West,” this film was my first thought. It is a retelling of Macbeth, using the stylized acting techniques, music, and expressions of nō theater.

Bentley: I was intrigued by the imagery of war-torn Japan overlaid with Macbeth.

Henn: Why has this film endured as one of Kurosawa’s classics?

Atkins: With the exception of his wartime films, Kurosawa’s films are always of interest to film buffs. People who take an interest in his work – including me – crave to see all of them. But although Kurosawa is a household name in Japan, he was not in his lifetime, nor is he now the most popular or well regarded director among Japanese audiences. There was a time when people criticized him as Japan’s most “Western” director, who made films for the international festival circuit. He always insisted he made his films for Japanese audiences, but his later work often depended on investors like George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg, or even the Soviet Union (!) for financing. “Throne of Blood” stands out among his oeuvre for its signature blend of nō aesthetics and its critique of individual ambition as a self-destructive force.

Bentley: I think it is because both cultures (British and Japan) appreciate the common theme. I think human nature is portrayed effectively here.

Henn: What is most striking in Kurosawa’s melding of Western tragedy and Japanese Noh Theatre?

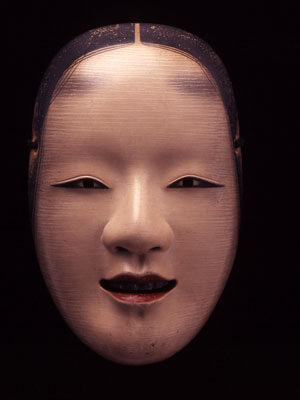

Atkins: For me, it’s Washizu’s wife Asaji and her unnerving lack of expression, which replicates the unmoving visage of a nō mask. When she does smile – exactly once, I think – you wish she hadn’t. It’s so sinister. The scene in which she tells Washizu that she is “with child” uses nō music to powerful effect, as well.

Bentley: The almost rhythmic movements, and the melodic imagery, to me, is the most striking.

Henn: What can viewers learn from this film about feudal period Japan or Japanese Noh Theater?

Atkins: I use this film whenever I teach about the Warring States period in Japanese history, roughly 1467-1590, which is the historical setting of the movie. “Ran” and “Kagemusha” are also set in that time, and I’ve used those as well, but I keep coming back to “Throne.” It’s an example of film as a “responsible” interpreter of history, whether or not it’s based on factual events or real people. It shows the cutthroat milieu of the Warring States, in which warlords (daimyō) came to power by ruthlessly murdering their lords, then spend most of their time worrying that someone among their retainers will do the same to them, rather than governing or enjoying their new status. It was later – in the 17th century – when loyalty became the cardinal virtue of the samurai; but at that time the country was at peace, warriors were bureaucrats and administrators, and some of them wrote about the ideals to which samurai should aspire. The writers of bushidō texts explicitly remembered the Warring States period as one in which treachery was far more common than loyalty, and constructed a value system encouraging nobler conduct.

Bentley: I think when people see the commonalities between Western and Japanese culture, they stop seeing Japanese culture as strange or exotic, and this then allows them to appreciate the things that are interesting or distinctive within Japan.

Bidou Yamaguchi. Zō-onna (Middle-Age Woman),1998. Japanese cypress, seashell, natural pigment, Japanese lacquer; (8.27×5.31×2.76 in.). Courtesy of Kelly Sutherlin McLeod and Steve McLeod Collection. © Bidou Yamaguchi.

William Shakespeare’s “Macbeth” serves as the source of the film’s plot, which has been transformed into the feudal period of Japan by stylistic elements from Japanese Noh theater.

General Taketoki Washizu, a Samurai warrior played by actor Toshiro Mifune, plays the lead role of Macbeth, spurred on by his wife, Lady Asaji Washizu, played by Isuzu Yamada, who seeks power and control of Spider’s Web Castle.

Kurosawa directed 30 films during his 57 year career which was critical in opening Western film markets to Japanese films and other Japanese filmmakers. He received a Lifetime Achievement Academy Award in 1990 for his contributions to cinema. Among his highly acclaimed films are “Ikiru” (1952), “Seven Samurai” (1954), “Kagemusha” (1980) and “Ran” (1985).

This film is not rated. Viewer discretion advised; film contains images of blood and violence.

This program is offered in conjunction with the exhibition “Traditions Transfigured: The Noh Masks of Bidou Yamaguchi,” a national traveling exhibition organized by the University Art Museum at California State University Long Beach in conjunction with Kendall H. Brown on display now at the NIU Art Museum.

For more information, call (815) 753-1936.