About 10 years ago, Nay Yan Oo was working toward a degree in computer science at the Government Computer College in Pathein, Myanmar.

But he kept running into a major snafu – access to a computer.

“I got a degree in computer science but didn’t get many chances to use the computer lab,” says the 28-year-old Nay Yan Oo. “That’s a problem.”

He and other students also lacked personal computers. When they did schedule lab time, they had to hope the electricity would be working that day. Nay Yan Oo often would end up writing computer code and never get a chance to see it work.

“You would run the program in your brain, not in the computer,” he says.

Now a graduate student at Northern Illinois University, Nay Yan Oo believes the situation for college students is improving in Myanmar, also known as Burma. But progress is happening slowly. Resources remain in desperate want as the country attempts to rebuild its university infrastructure, devastated by a half-century of isolation from the outside world.

NIU, which specializes in Southeast Asian studies and operates the only Center for Burma Studies in the United States, is now among the American universities at the forefront of efforts to assist their counterparts in the once closed society as it emerges from decades of rule by military dictatorship.

Over the last 18 months, eight NIU faculty members, including Provost Lisa Freeman and College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Dean Chris McCord, have visited Myanmar universities and lectured in the country, with some making multiple trips.

McCord has been to Myanmar twice and was among 35 international education professionals who volunteered to participate in a recent pilot course led by the Institute of International Education (IIE). Titled “Connecting with the World,” the 20-week course sought to address a pressing need to develop international offices on university campuses in Myanmar.

The training is seen as an essential step to enable Myanmar universities to connect with institutions abroad, build institutional capacity, prepare their students to meet workforce needs and support rapid economic development.

Volunteers worked with Myanmar participants as “virtual mentors,” engaging in weekly email correspondence about course assignments. Lessons covered topics ranging from facilitating student and faculty exchange to developing institutional agreements.

McCord mentored an electrical engineering professor who was tasked with creating an international office. He had no prior experience whatsoever in international education.

“We talked about very basic concepts, such as what it means to have an international relations office and how to navigate cultural differences,” McCord says.

“It was challenging, and I think it demonstrates just how oppressed Myanmar society had been. Faculty members there don’t have these skills sets because this is something they weren’t allowed to do. I was asking my mentee to imagine things that, in the past, could have gotten him arrested.”

The “Connecting with the World” effort was in response to needs identified during a IIE-led delegation to Myanmar in February 2013.

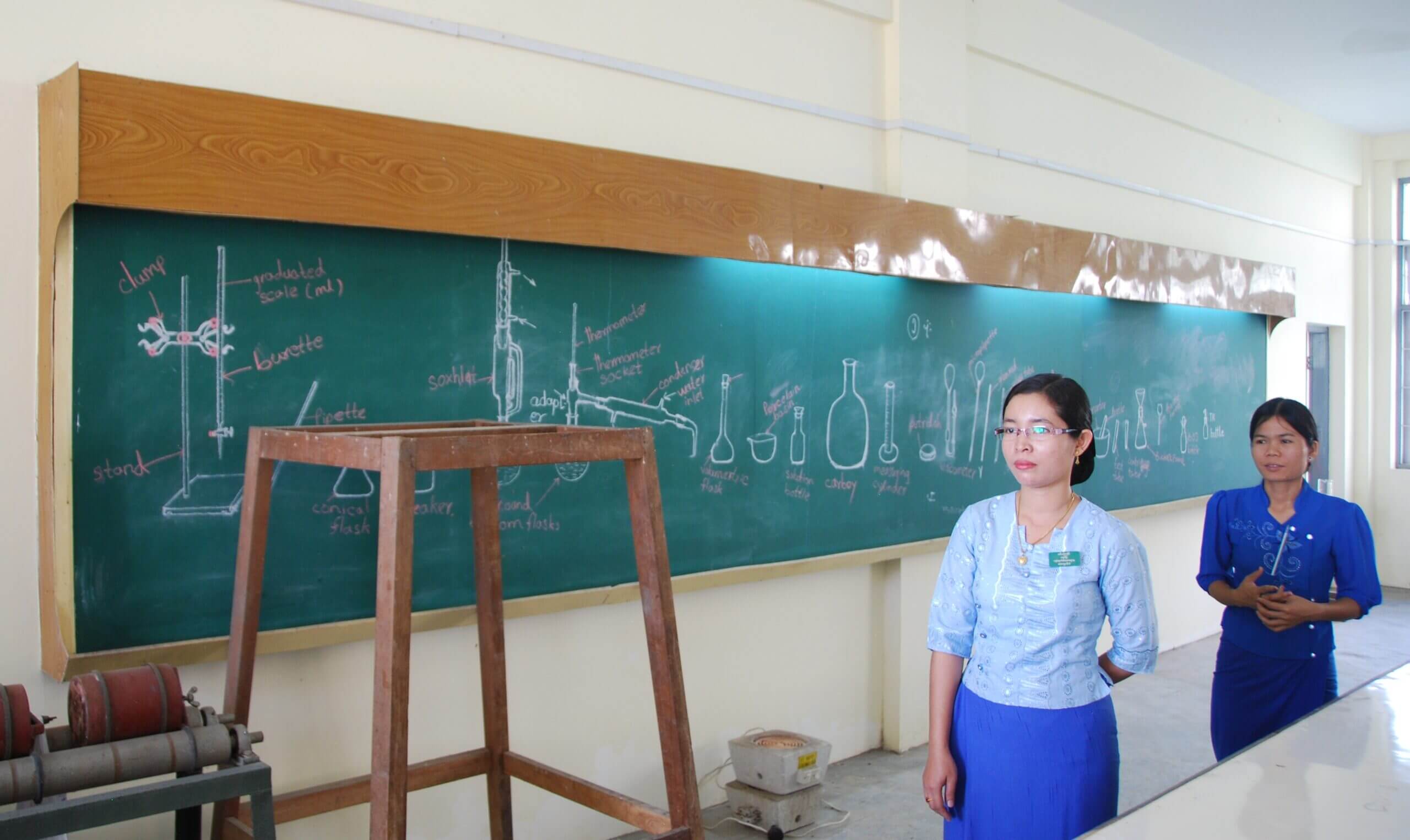

McCord, who was among the delegates, says the need to help the country rebuild its damaged university infrastructure was driven home on that trip when he visited a chemistry class at Dagon University in Yangon, the country’s largest city.

“On the chalkboard, we saw drawings of chemical apparatus like flasks and test tubes. The drawings were there because they don’t actually have any real equipment to use in class,” McCord says. “It’s just one small detail among many that points to the tremendous need for capacity building in Myanmar higher education.”

Some Myanmar educators must make-do with chalkboard illustrations instead of real equipment in a chemistry lab.

Prior to the 1960s, Myanmar boasted an impressive university system. But it was undone by the military junta that viewed universities as breeding grounds for political unrest.

Following 1988 uprisings, the government shut down the country’s universities. Some reopened two years later, but with government-controlled curriculum. Universities were closed again for a 3-year period beginning in 1996, according to the Oxford Burma Alliance.

“We never had political science departments in our country starting from 1988, and they have only recently returned,” says Nay Yan Oo, who is studying political science at NIU and hopes to some day run for office in Myanmar.

Political and economic reforms began in Myanmar in 2012. And with those reforms, the country has begun to open its doors.

“The government realized our education system had fallen behind,” Nay Yan Oo says, adding that officials are interested in bringing more foreign scholars to the country.

Catherine Raymond directs NIU’s Center for Burma Studies, which serves as the national repository for Burmese items donated to the Burma Studies Foundation.

“The most educated people in Myanmar now have been educated abroad, whereas before it used to be very different,” says Raymond, who in July will make her fifth trip to Myanmar since early 2013.

Raymond also will host six librarians from Myanmar universities visiting NIU this summer and fall to learn about library logistics. During her previous visits, she says, she found that university libraries were sorely lacking in the resources they’re known for – namely, books.

“They didn’t have access to current research or books,” Raymond says. “Some faculty members were using texts dating back 50 years, and they lacked easy access to computers and the Internet.”

Dean McCord says Myanmar faculty and students are eager to jump-start university research and international education, and he’s proud that NIU is facilitating.

Among the university efforts:

- NIU rescued and returned to Myanmar a nearly 1,000-year-old, Buddha statue that had been stolen from a temple in 1988.

- English chair Amy Levin traveled to Myanmar in 2013 on a Fulbright fellowship, teaching a series of workshops and working with faculty and students as the first U.S. professor of literature to collaborate on a Fulbright with universities there in 30 years.

- Raymond, along with NIU Burmese language professor Tharaphi Than, political scientist Kheang Un and Center for Southeast Asian Studies director Judy Ledgerwood, lectured at several Myanmar universities last summer on topics ranging from gender studies to democracy to research methods. Tharaphi Than is returning this summer to present a workshop at Yangon University.

- This past spring, the university hosted five teenagers from Myanmar who took part in the Southeast Asia Youth Leadership Program on campus.

- NIU recently signed a memorandum of understanding to collaborate with Yadanabon University, one of the first such agreements between a U.S. university and Myanmar counterpart.

- Geology professor Melissa Lenczewski, director of NIU’s Institute for the Study of the Environment, Sustainability and Energy, is traveling to Yadanabon University this month to deliver donated equipment for testing of water quality and to conduct equipment training.

- Raymond and anthropologist Andrea Molnar will spend a week in July at Yangon and Yadanabon universities, delivering lectures and working with Myanmar colleagues.

- History professor Kenton Clymer taught at Yangon University in December and will soon publish a book with Cornell University Press on the history of U.S.-Burmese relations since WWII.

“We are really looking at this as a unique opportunity to make a real difference and help people who are really passionate about rebuilding their higher education system,” McCord says. “It all makes sense, since this happens to be in an area of the world where we have a high level of expertise.”