What won’t Mitch Irwin do in the name of science?

Irwin, a Northern Illinois University anthropologist, went to great lengths to collect data in Madagascar for a fascinating new study that sheds light on why primates live long lives.

An international team of scientists working with primates in zoos, sanctuaries and in the wild examined daily energy expenditure in 17 primate species, from gorillas to mouse lemurs, to test whether primates’ slow pace of life results from a slow metabolism.

Using a safe and non-invasive technique known as “doubly labeled water,” which tracks the body’s production of carbon dioxide, the researchers measured the number of calories that primates burned over a 10-day period. Combining these measurements with similar data from other studies, the team compared daily energy expenditure among primates to that of other mammals.

For his part, Irwin dosed and tracked lemurs in Madagascar, which he has studied over the past 14 years with his wife, NIU biological sciences professor Karen Samonds. They accomplished the initial injection during routine capture and health exams, but needed periodic fluid samples over the following week to get a measurement.

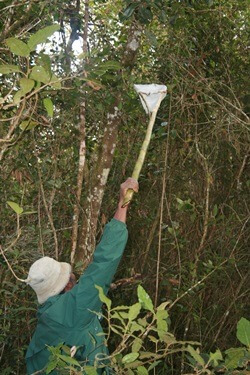

“It was pretty tricky for our teams because we had to catch urine from the lemurs on the go, which was all but impossible,” Irwin says. “We settled on a technique using plastic bags attached to 12-foot bamboo poles. Usually the lemurs would urinate too high in the forest canopy, and we’d get nothing. But with perseverance we got enough samples to contribute to the database.”

The new research shows that humans and other primates burn 50 percent fewer calories each day than other mammals. The study, published in the “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,” suggests that these remarkably slow metabolisms explain why humans and other primates grow up so slowly and live such long lives.

The study also reports that primates in zoos expend as much energy as those in the wild, suggesting that physical activity might have less of an impact on daily energy expenditure than is often thought.

“I think the research will have broad impact,” Irwin says. He’s listed as an author on the PNAS study, but says the research was primarily driven by anthropologists Herman Pontzer of Hunter College in New York and Dave Raichlen of the University of Arizona.

“I had known them for years, and they knew that capturing lemurs was part of my ongoing research, so it was a good fit,” Irwin says.

Most mammals, like the family dog or pet hamster, live a fast-paced life, reaching adulthood in a matter of months, reproducing prodigiously (if we let them), and dying in their teens if not well before. By comparison, humans and their primate relatives (apes, monkeys, tarsiers, lorises and lemurs) have long childhoods, reproduce infrequently and live exceptionally long lives.

Primates’ slow pace of life has long puzzled biologists because the mechanisms underlying it were unknown.

“The results were a real surprise” says Pontzer, lead author of the study. “Humans, chimpanzees, baboons and other primates expend only half the calories we’d expect for a mammal. To put that in perspective, a human – even someone with a very physically active lifestyle – would need to run a marathon each day just to approach the average daily energy expenditure of a mammal their size.”

“The results were a real surprise” says Pontzer, lead author of the study. “Humans, chimpanzees, baboons and other primates expend only half the calories we’d expect for a mammal. To put that in perspective, a human – even someone with a very physically active lifestyle – would need to run a marathon each day just to approach the average daily energy expenditure of a mammal their size.”

This dramatic reduction in metabolic rate, previously unknown for primates, accounts for their slow pace of life. All organisms need energy to grow and reproduce, and energy expenditure can also contribute to aging. The slow rates of growth, reproduction, and aging among primates match their slow rate of energy expenditure, indicating that evolution has acted on metabolic rate to shape primates’ distinctly slow lives.

“The environmental conditions favoring reduced energy expenditures may hold a key to understanding why primates, including humans, evolved this slower pace of life,” Raichlen says.

“What’s particularly interesting is that primates use the same amount of energy as other mammals of the same size when resting,” says co-author Adam Gordon, an anthropologist at the University at Albany. “So primates’ later age at maturity and extended life span are related to total energy expenditure, rather than to baseline energy needs as one might expect.”

Perhaps just as surprising, the team’s measurements show that primates in captivity expend as many calories each day as their wild counterparts. These results speak to the health and well-being of primates in world-class zoos and sanctuaries, and they also suggest that physical activity may contribute less to total energy expenditure than is often thought.

Samonds and Irwin helped found Sadabe, an NGO developing innovative ways to promote the healthy coexistence of humans and wildlife in Madagascar.

“The completion of this non-invasive study of primate metabolism in zoos and sanctuaries demonstrates the depth of research potential for these settings. It also sheds light on the fact that zoo-housed primates are relatively active, with the same daily energy expenditures as wild primates,” said co-author Steve Ross, director of the Lester E. Fisher Center for the Study and Conservation of Apes at Chicago’s Lincoln Park Zoo.

“Dynamic accredited zoo and sanctuary environments represent an alternative to traditional laboratory-based investigations and emphasize the importance of studying animals in more naturalistic conditions.”

Results from this study hold intriguing implications for understanding health and longevity in humans.

Linking the rate of growth, reproduction and aging to daily energy expenditure might shed light on the processes by which our bodies develop and age. Meanwhile, unraveling the surprisingly complex relationship between physical activity and daily energy expenditure might improve our understanding of obesity and other metabolic diseases.

More detailed study of energy expenditure, activity and aging among humans and apes is already under way. “Humans live longer than other apes, and tend to carry more body fat” Pontzer says. “Understanding how human metabolism compares to our closest relatives will help us understand how our bodies evolved, and how to keep them healthy.”

Related: