If there’s strength in numbers, Chicago’s outer-ring towns gained big-time muscle from 2000 to 2010, according to a new analysis of census data by NIU geography professor Richard Greene.

If there’s strength in numbers, Chicago’s outer-ring towns gained big-time muscle from 2000 to 2010, according to a new analysis of census data by NIU geography professor Richard Greene.

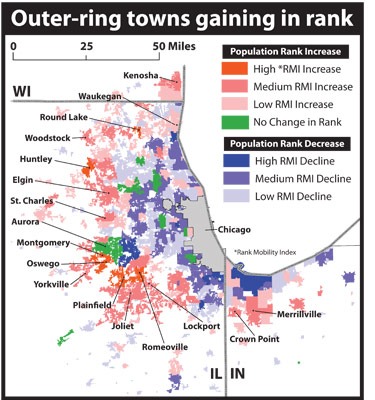

During the century’s first decade, well-established edge communities such as Joliet, Aurora, Elgin, Waukegan and Kenosha added to their already burgeoning populations and strengthened their positions atop the regional population hierarchy, Greene says.

Meanwhile, many smaller edge communities experienced explosive growth, led by Plainfield, Huntley, Oswego, Montgomery and Yorkville. Located northwest of Elgin, little Pingree Grove was a hamlet of 124 residents in 2000. Over the next decade it grew by a whopping 3,555 percent, to 4,532 people.

Rapid growth in outer-ring communities or edge cities, in fact, more than offset areas of population decline within the greater metropolitan area, including within the City of Chicago.

Between 2000 and 2010, Chicago lost more than 200,000 residents while many inner suburbs also declined in population, Greene says. Yet, bolstered by edge cities, the Chicago metropolitan area as a whole grew by 4 percent. The two largest outer-ring communities in the Chicago region — Aurora and Joliet — together added nearly 100,000 residents.

Aurora held its ground as the largest population city in the metropolitan area outside of Chicago, while Joliet (2), Elgin (4), Kenosha (5) and Waukegan (6th) all moved up one notch.

Hispanic population growth played an important role in increasing the populations of Aurora and Elgin, Greene adds. The center of each of those cities is located in Kane County, where Hispanics represent 31 percent of the population, almost double the national average of 16 percent.

“The story behind population growth is a little different from one community to the next, but all of the towns that moved up significantly in population dominance typically shared one common characteristic — they had room to grow,” Greene says.

RMI: Power rankings

To visually identify towns and regions that are growing in population dominance, the NIU professor, who specializes in the study of urban geography, revisited a 2006 study he had conducted, this time plugging in 2010 census data.

The study utilizes a Geographic Information Systems analysis to determine and map out the change in population rank, or Rank Mobility Index (RMI), of each town in the Chicago metropolitan area. (RMI values range from -1.0 to +1.0.)

“The geo-visual mapping of the RMI values clearly depicts the growing population dominance of the outer-ring communities – as well as continued suburban sprawl over the past decade,” Greene says.

Rather than simply looking at the percentages of population change, the RMI identifies substantial moves in population rank, allowing local governments, politicians and economic groups to identify potential redistributions of resources across a region. Communities that are growing in population tend to enjoy the benefits of growth, such as newer infrastructure, increasing revenue bases, more state and federal funding and more voting power, Greene says.

“The use of the RMI is especially appropriate for studying the changing dominance of suburbs,” he says. “A rank increase represents a power shift, and we’re generally seeing a repositioning of power, with declining population ranks for inner suburban clusters and increasing ranks for edge communities.”

Among the larger cities, Joliet, which replaced Naperville as the second largest city in the region surrounding Chicago, registered the highest RMI value. “A rank change carries more weight when it is higher on the list of rankings. That’s because the larger the city, the more difficult it is to overtake in rank,” Greene explains.

The RMI doesn’t always reflect population growth or decline. Naperville grew by 13,495 residents but registered a negative RMI value because it dropped in rank, from second to third.

“One of my graduate students did a study showing how the city is now almost completely boxed in by its neighbors,” Greene says. “The story of Naperville is the same as Chicago — basically it’s landlocked.”

Small towns no more

Overall, the highest RMI values belonged to the smaller but fast-growing suburbs of Plainfield, Romeoville, Huntley, Oswego, Montgomery, Round Lake, Yorkville and Lockport. Each of those communities made huge leaps in the region’s population rankings.

Plainfield had the highest RMI score out of 371 suburban communities in the metropolitan region. In 2000, Plainfield ranked 138th in population. By the decade’s end, it was the 36th largest town, having tripled its population, to 39,581 residents.

It was no coincidence that three of the leading RMI communities — Plainfield, Oswego and Montgomery — also intersect Kendall County, the nation’s fastest growing county from 2000 to 2010.

“These towns have climbed up in the region’s hierarchy for a variety of reasons, including great access to highways,” Greene says. “Importantly, they also were able to acquire new territory because they had less resistance on their peripheries.”

Nine towns that became newly incorporated during the first decade of 2000s

Poised for more growth?

One large city in particular still has plenty of room to grow, according to Greene. “Joliet is the one to watch in the future,” he says.

Whether growth is beneficial to a community depends on a number of variables, Greene adds. But significant population declines are cause for concern because tax revenues decline, providing less support for already established businesses and community infrastructure.

“Generally speaking, if a community is moving up in rank, there’s a better chance that it’s fiscally healthy,” Greene says.

“But even that rule of thumb is not always true. The 2010 census came on the heels of a severe recession that halted growth and spurred a rash of foreclosures. Smaller edge communities might have experienced residential growth without realizing the full benefits of growth in the retail and commercial sectors, which always lag behind.”

Sprawl is another concern.

“In 2000, urban planners were hoping for a resurgence of downtown areas,” Greene adds. “Generally speaking, what we got was more sprawl and a move away from the center. That was the story of the 2010 census for the Chicago metropolitan area.”