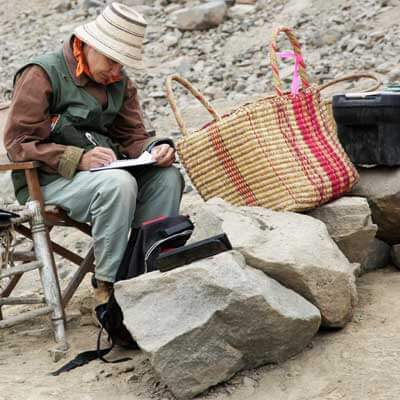

NIU anthropologist Winifred Creamer “in her office”

at the Huaricanga dig site in Peru.

Credit: Jonathan Haas

A new study by a team of archaeologists that includes Northern Illinois University anthropologist Winifred Creamer provides convincing evidence that the earliest civilization of South America relied heavily on agriculture – specifically the large-scale production of corn.

For decades, researchers have debated whether the people who lived on or near the Pacific coast of Peru during the Late Archaic period (3000-1800 B.C.) subsisted primarily on fish or whether maize was cultivated and used as a regular part of their diets.

The new study uses microscopic evidence from pollen records, coprolites and stone-tool residues to demonstrate that maize was widely grown, intensively processed and constituted a primary component of the early Peruvians’ diet.

The study is published in the online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

“It’s long been thought that the ancient Peruvians took a unique pathway to civilization, relying on a surplus of fish and other seafood that formed the basis of their economy,” Creamer said.

“The new evidence shows that the start of civilization in South America was actually powered by agriculture, just as in the other great early civilizations, such as in Mesopotamia and Egypt,” she added. “The common element among all these ancient world powers was grain, which produced a reliable yield and was easy to store. In ancient Peru, we found that corn was everywhere. It was a staple of their diets and a key part of this civilization’s economy.”

Creamer co-directed the research project with her husband and lead PNAS article author Jonathan Haas, MacArthur curator of the Americas at the Field Museum in Chicago and adjunct faculty member at NIU.

The study focused on archaeological sites in the sand-swept Norte Chico region of north-central Peru, from the Andes to the western coastline. The region is believed to be the place where cultural evolution in the Andes – and in the Americas, for that matter – first diverged from simple hunting and gathering into complex society.

Creamer and Haas have been among those whose archaeological work has brought into focus the civilization that arose more than 5,000 years ago in three small valleys 100 miles north of Lima. Over more than a millennium, the region saw the development of 30 separate major residential centers, characterized by large pyramid-like structures, circular ceremonial courts, temples and housing.

For more than 40 years, the economic importance of maize in this early civilization has been debated. The lack of much visible evidence of the grain’s presence at the ancient sites led to the interpretation that it was used primarily for ceremonial purposes.

“The first archaeological sites identified in Peru were on the coast, but within the last 15 years, more and more ruins from this early time were discovered inland,” Creamer said. “If it was really a civilization based on a fishing economy, we wouldn’t expect such large sites and so many sites away from the coast. That led to the idea that perhaps agriculture was more important than archaeologists originally suspected.”

The new study is based on excavations between 2002 and 2008 at 13 sites in the desert valleys of Pativilca and Fortaleza north of Lima. The two most extensively studied sites were Caballete, about six miles inland from the Pacific Ocean, and Huaricanga, about 14 miles inland. The scientists took samples from ancient residences, trash pits, ceremonial rooms and campsites and found an abundance of microscopic evidence of maize in various forms.

The first line of evidence came from the recovery of maize pollen in samples of soil from the ancient sites. While maize is grown in the region today, the researchers were able to rule out modern day contamination because of differences in contemporary maize pollen grains.

Of the 126 soil samples analyzed, 61 contained the ancient maize pollen. This is consistent with the percentage of maize pollen found in analyses from sites in other parts of the world where maize is a major crop and constitutes the primary source of calories in the diet.

Excavations at Caballete provided one of the primary sources of

coprolites and tools containing evidence of maize.

Credit: Jonathan Haas

The pollen data are complemented by an analysis of residue found on ancient stone tools used for cutting, pounding and grinding. Eleven of 14 tools recovered from the Caballete site had predominantly or exclusively maize starch grains on the working surfaces. Two tools also had starch grains of sweet potato, and three had starch grains of beans.

“They were grinding beans and sweet potatoes and using a whole range of other plants,” Creamer said. “This was a mature agricultural society.”

Direct evidence for the consumption of maize was found in human coprolites (preserved fecal matter) recovered from both Caballete and Huaricanga. Of 34 human coprolites tested, more than two thirds contained maize starch grains. Significant percentages of animal coprolites, including from domesticated dogs, also tested positive for corn starch grains.

“If dogs and wild animals were eating maize, it was all around,” Creamer says. “The combined evidence makes it clear that corn was an important part of the diet of these ancient Peruvians.”

All of the botanical work conducted for the study was carried out at the new Laboratorio de Palinología y Paleobotánica at the Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, under the direction of Luis Huamán. Analysis of the botanical remains was a collaboration between Huaman, David Goldstein of the National Park Service, Karl Reinhard of the University of Nebraska and Cindy Vergel of the Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia.

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation, as well as NIU, the Field Museum and private donors.